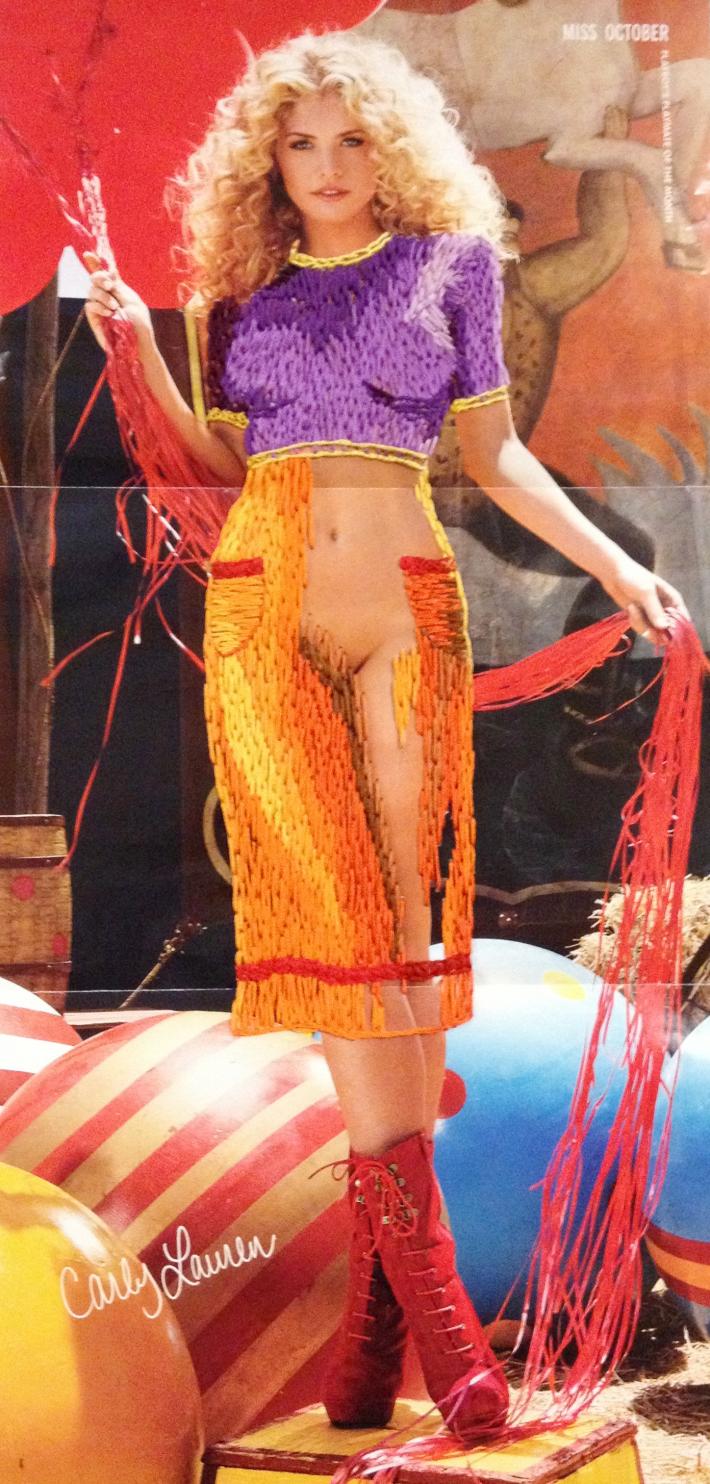

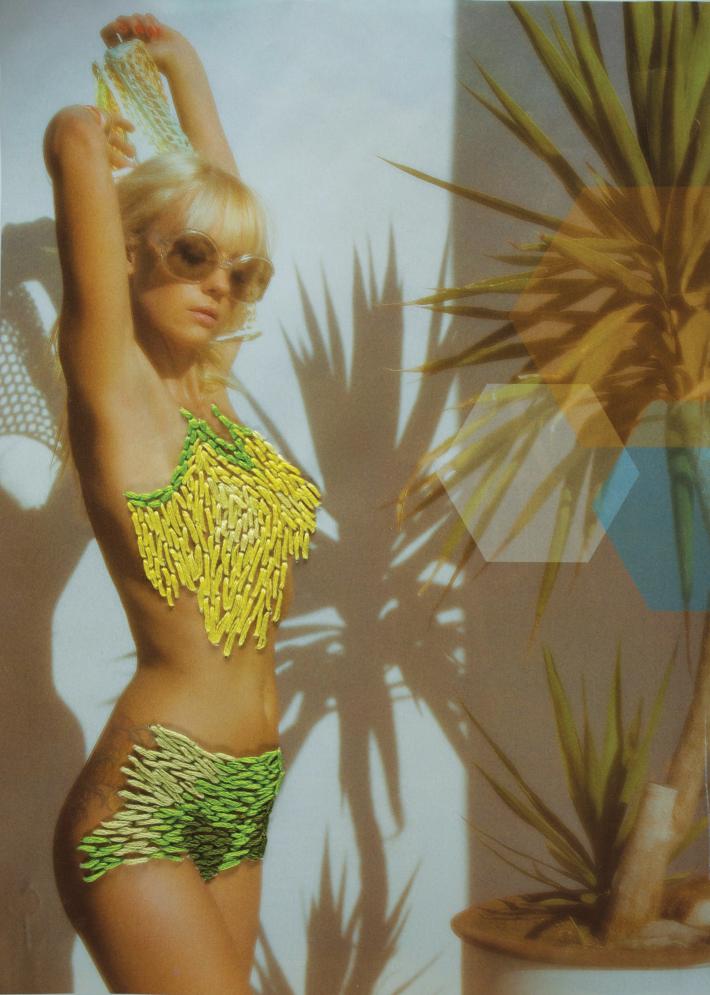

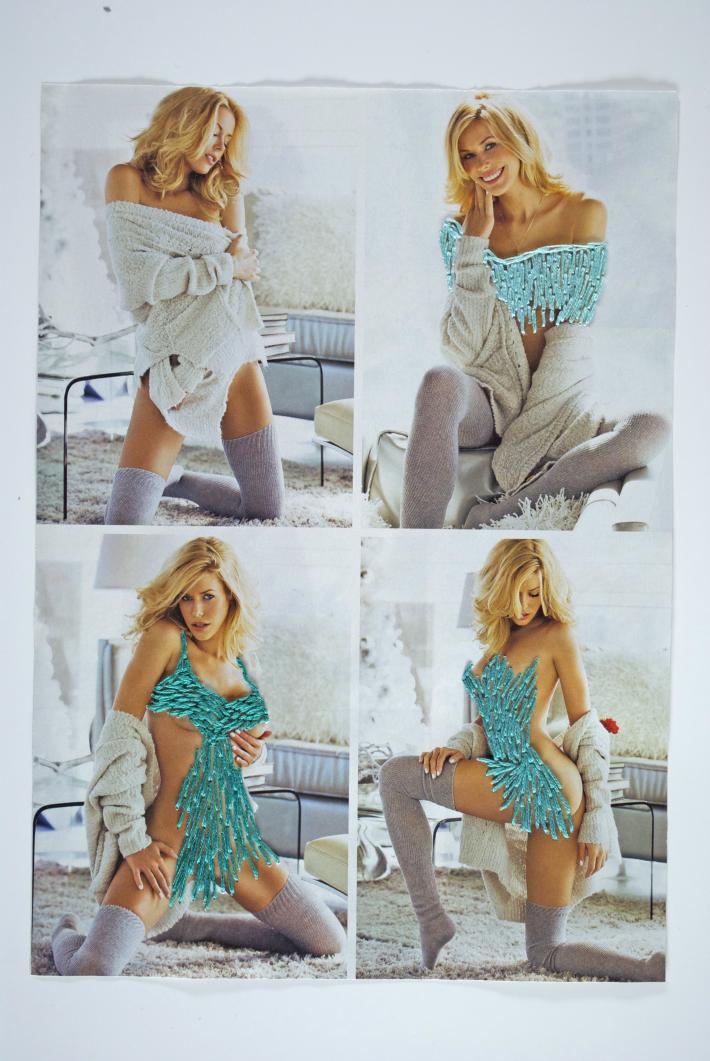

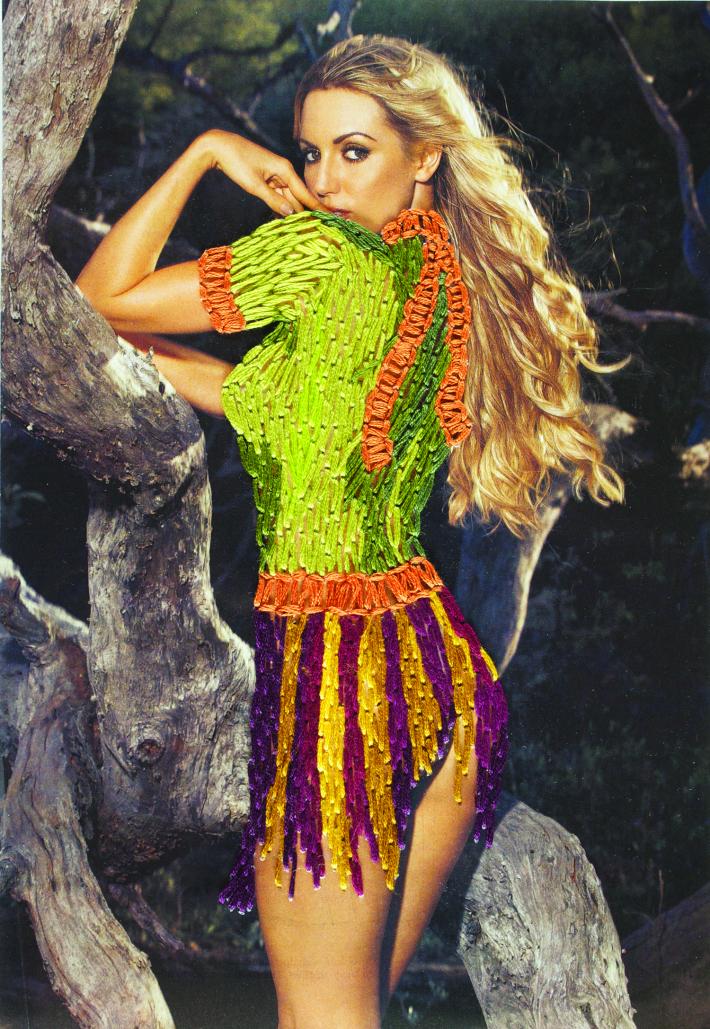

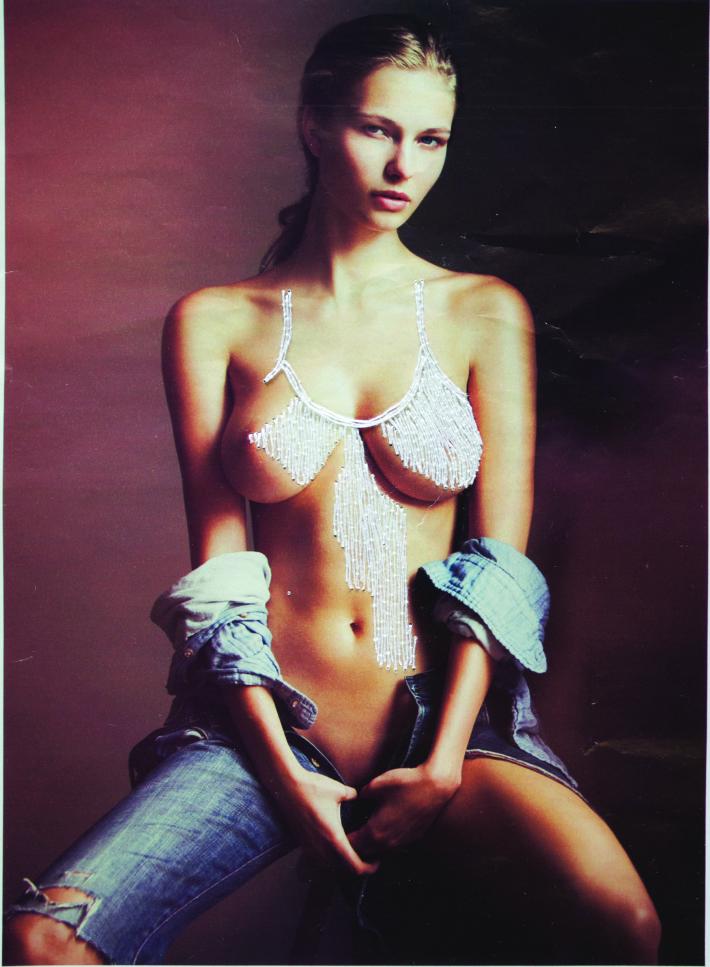

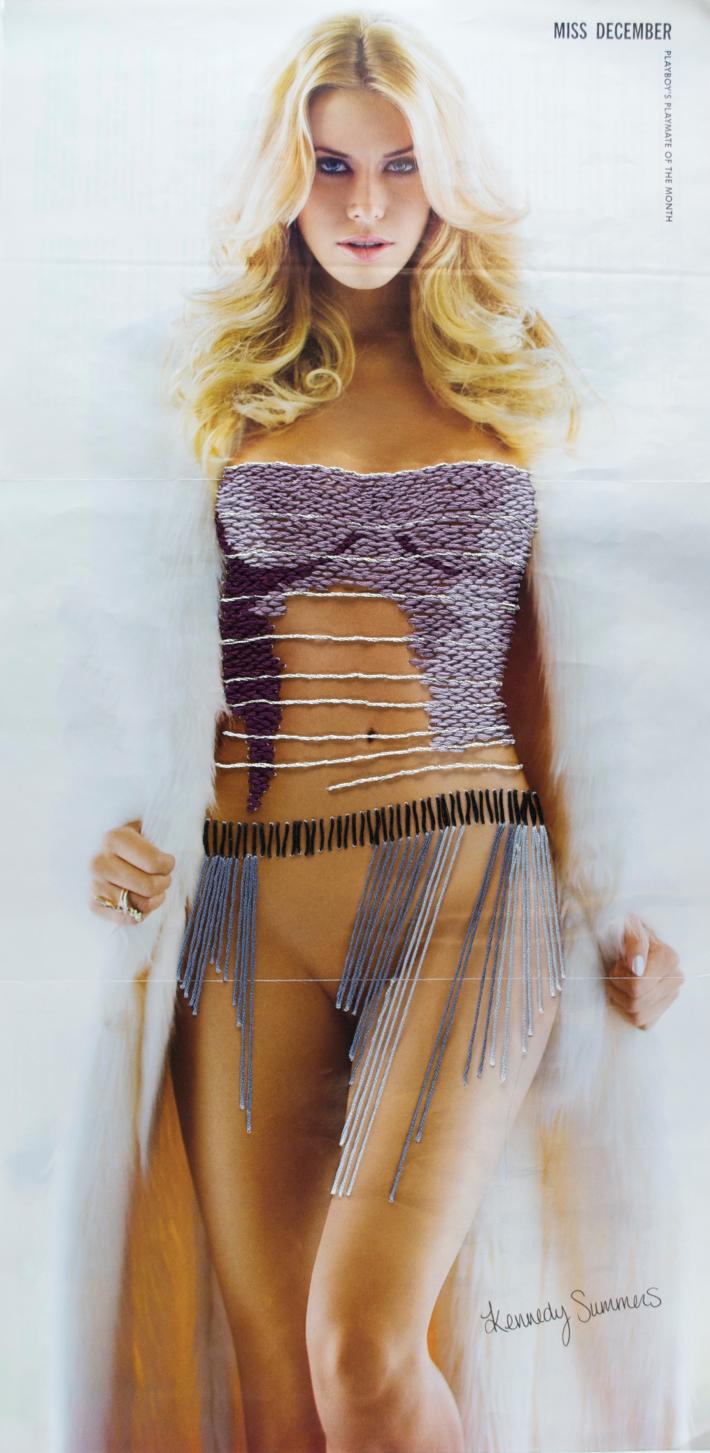

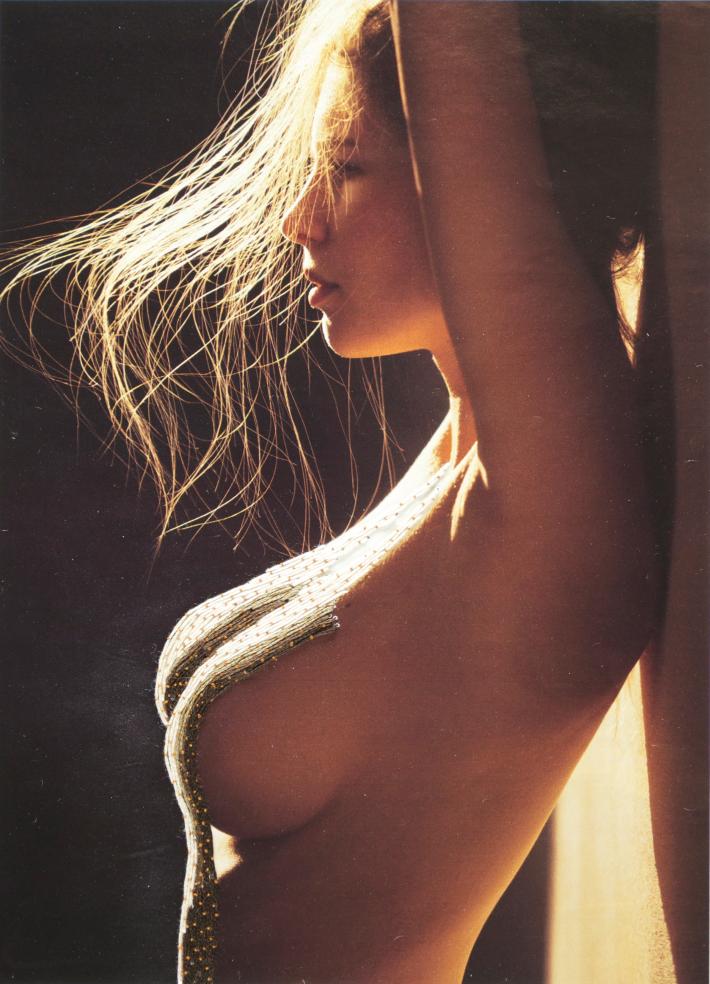

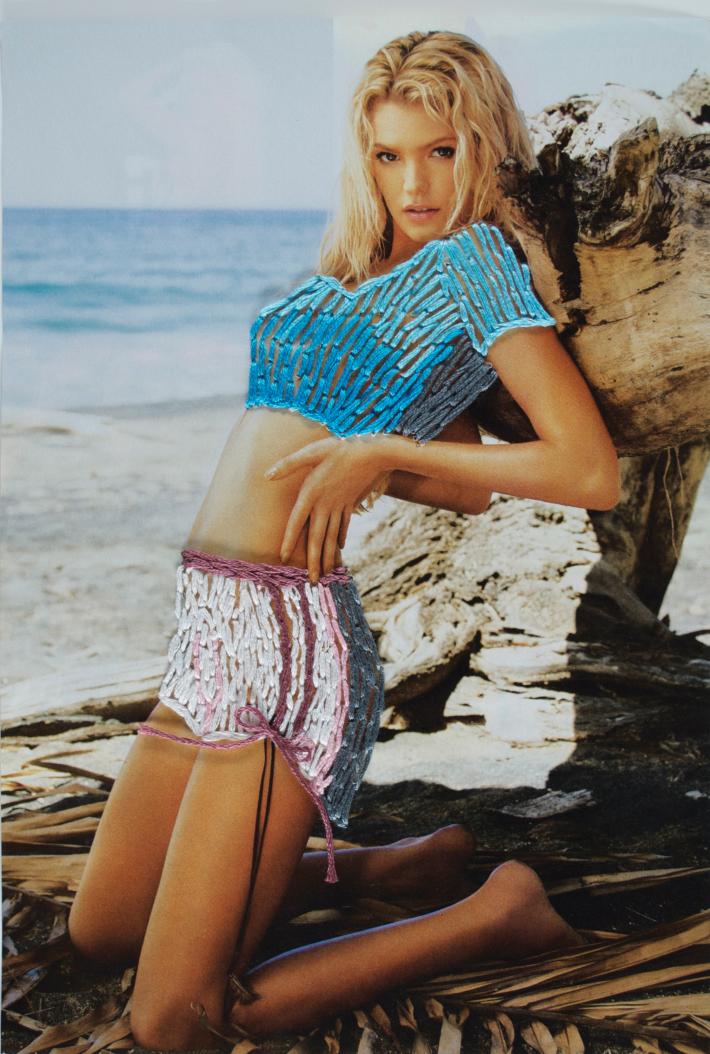

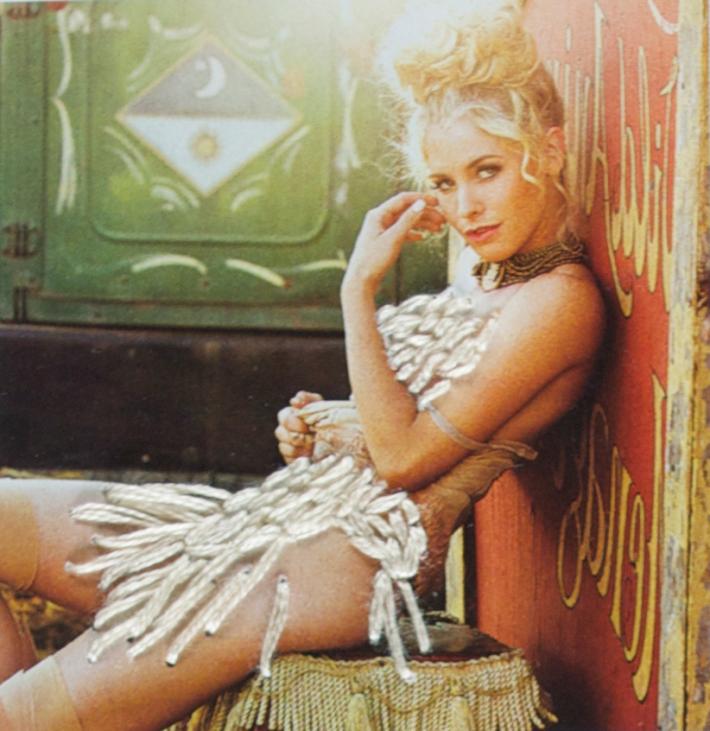

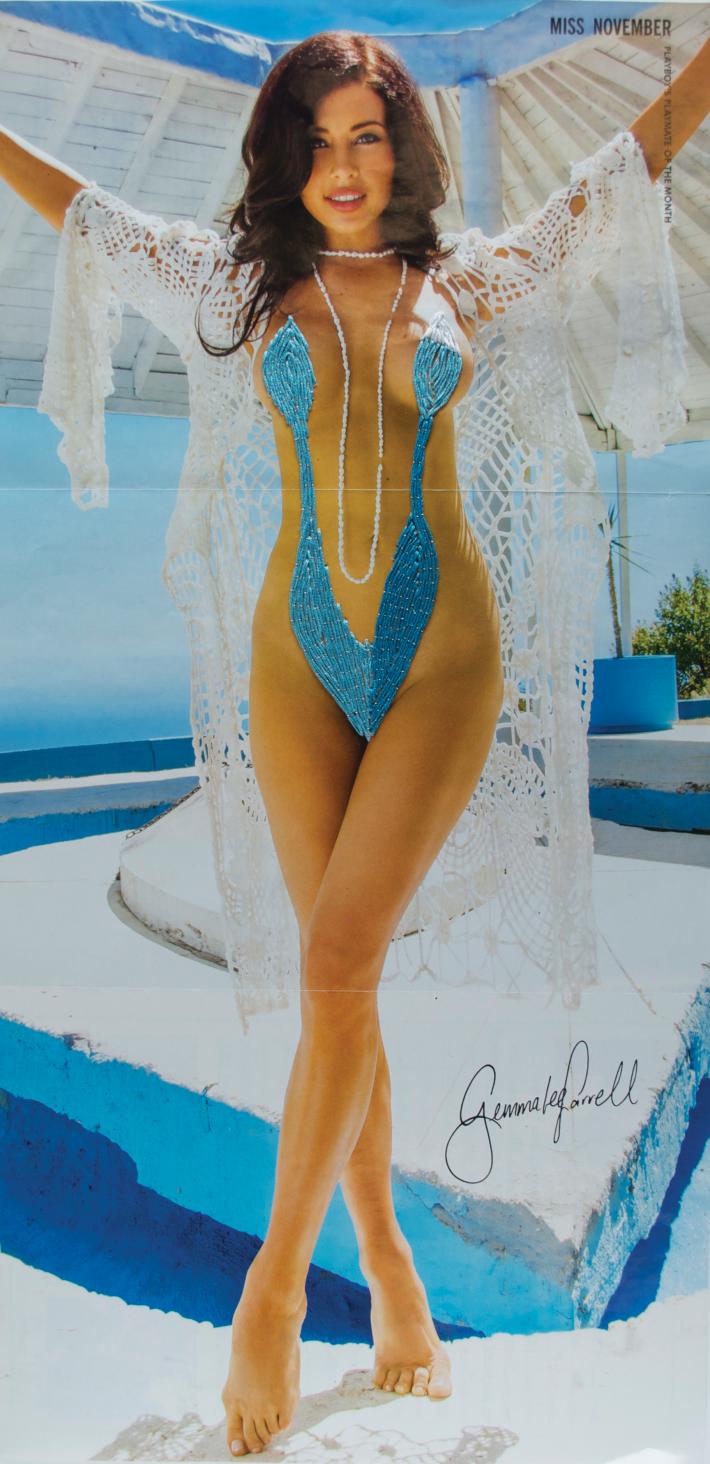

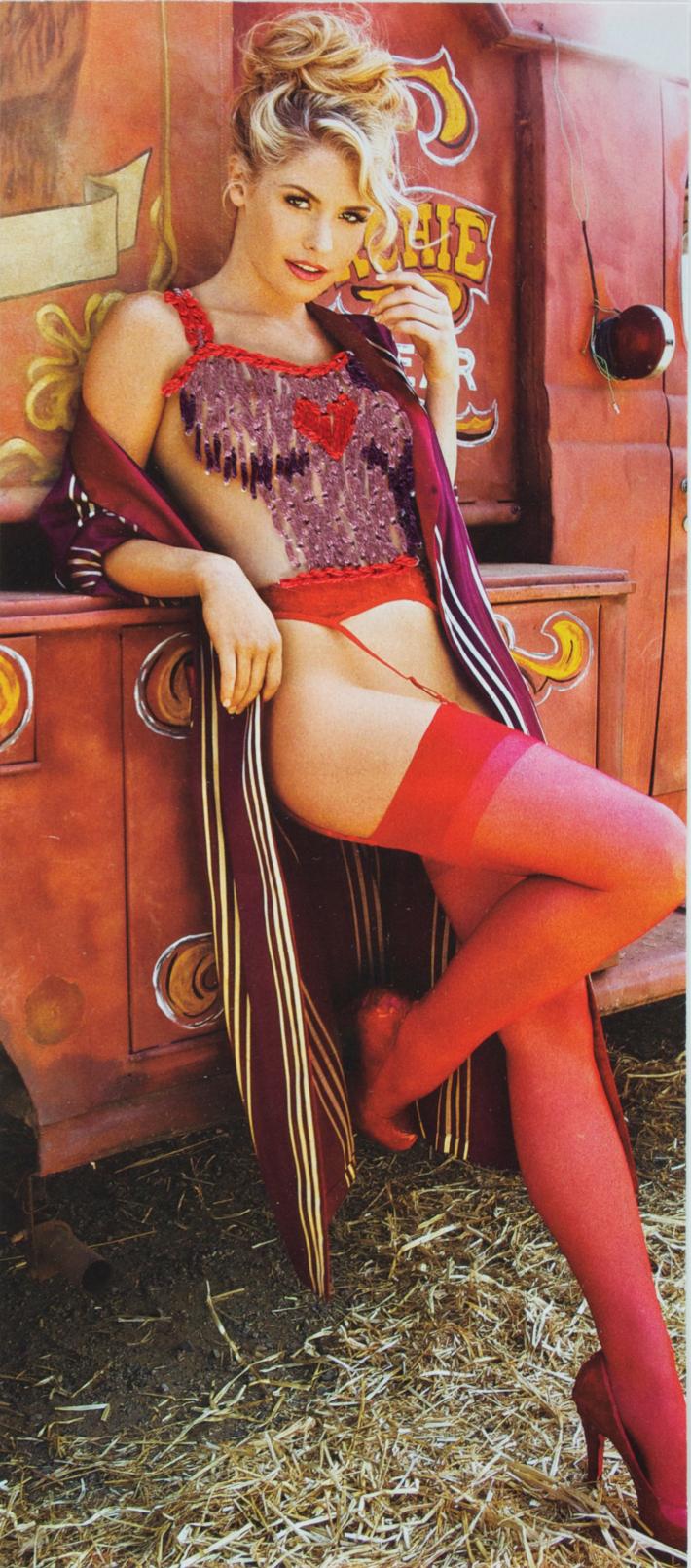

Virgin|Whore Series

Needlework, specifically embroidery is used on images from Playboy Magazine as an attempt to shift the models from object to entity. The irony lies in the fact that both of these elements (embroidery and Playboy models) are symbols of female oppression and objectification. The materials and imagery are in constant opposition and obedience with each other.

These pieces were done as part of my thesis work over the span of 2013 to 2015. They have since been part of a personal exhibit Mending in 2015 in Toronto. Some are still available for purchase. Below is some of the writing that has been culled from both the thesis paper as well as the exhibit catalogue.

Since the Victorian Age, needle-work has become highly gendered, constructed as women’s work, and is seen as a symbol of obedience. It is perceived to be an act that is done quietly, patiently with eyes down. The early twentieth century French author Colette alludes to the repressive act of sewing when she writes about teaching her nine year old daughter how to sew after her friends expressed that, by not doing so, she was failing as a mother:

"Silent when she sews, silent for hours on end, with her mouth firmly closed... She is silent, and she—why not write down the word that frightens me—she is thinking" (1).

Sewing elicits specific socially constructed ideals that can be traced back to the Victorian era. Sewing was done by wives. It was seen to be part of ‘housewifery’ (2).

Men did sew but it was done in a different context than women. Larsen describes the separation of male and female needlework:

"Once textiles came to be seen as women’s work, plain sewing and all forms of needlework became subordinate, feminized, inappropriate occupations for men, or at least straight men. Exceptions are found in the history of industrialized fibre-related occupations that were and are open to all men without stigma (3).

Masculine needlework would have included the crocheting of fishing nets, furniture upholstery and tailoring. This divide was mostly due to the physical strength required to work with materials such as fishing nets and furniture as well as the aspect of trade which was a part of a public life in which women were not historically encouraged to engage. The quality of a woman’s sewing was seen as a symbol of her abilities as a wife. Hedges asserts that the pen is symbolic of independence and intelligence while the needle remains symbolic of the confinement associated with domestic life (4). Thus sewing is considered an act of obedience carried out by women and is consequently tied to female oppression. However, there are other scholars who see it differently.

Goggin argues that needlework, which is associated with mundane daily tasks, has been ‘mistakenly assumed unworthy of scholarly attention’ (5). She goes on to state:

"The powerful ideological construct of needle-work as ‘woman’s work’ and all that term has come to mean and the pejorative baggage it carries, obscures the richness of this practice as a potential rhetorical tool" (6).

Goggin sees how needlework allows for reflection on the part of the maker, is a form of self-expression, and provides a manner of autonomy. All of which is worthy of study.

The needlework in the Virgin|Whore series is in agonistic discourse with itself and the imagery that it subverts. Pages from Playboy Magazine depicting nude female models are stitched so as to cover the commodified naked bodies of the models. This attempt to shift the women from object to entity is ironically done using a symbol of female oppression—needlework.

The materials being seen in these works are in opposition with each other. Thread is used in every piece but is combined with unexpected, non-traditional materials. Stitching is usually done on fabric where the weave restores itself after the needle has slipped through. Fabric is malleable and can be gripped and handled fairly aggressively. Conversely, magazine paper is not meant to be sewn and thus retain the holes that the needle creates and, when the thread is pulled too hard, the tears. Furthermore, constant handling of inexpensive magazine paper affects the the surface—it creases, weakens and buckles—ingraining the hand of the maker in the work long after its completion.

Pristash, Schaechterle and Wood discuss how the act of stitching is meaningful:

"In the discussion of rhetorical needlework, the process is typically at least as important to study as the product, if not more so… After all, while intentionality may, often quite fairly, be derived from an educated reading of the final object, it is in the reasons for and the methods of an objects creation that intentionality is first born" (7).

Pristash et al., illustrate how the physical acts involved in handcraft techniques hold meaning. The processes of stitchery in the Virgin|Whore works are deliberate and required hours of sitting and sewing. Every stitch is planned and placed, the needle piercing representations of naked women, which can be viewed as a punishment for their promiscuity. Yet with each stitch the female bodies are concealed, the thread forming a blanket of protection and pardon—an act symbolic of the mother. Moreover, sewing is often used for mending articles that are worn, ripped or frayed. Thus these stitches can be read as a form of reparation. Parker explains that embroidery ‘evokes the stereotype of the virgin in opposition to the whore’ (8) In this series of work the virgin and whore stereotypes are represented in both the artifact and the act, and both are battling with the roles that society has allotted them.

Many craft theorists discuss the oppositional play involved in using handcraft techniques in contemporary contexts. The rich dichotomy between techniques, technology and ideology is evident in these hand-sewn works. However, the bright colours and playful interaction between handcraft and digital technology of the works are betrayed by a darker undertone. The works insinuate the issues that are still plaguing handcraft, as well as women—the perception that handcraft is a lower form of artistic production and the oppression and objectification of women.

(1) Rozsika Parker, The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine, (New York: The Women’s Press, 1984), 10.

(2) Ibid., 90.

(3) Anna-Marie Larsen, “Boys With Needles,” Craft: Perception and Practice. Volume 2. Ed. Paula Gustafson, (Vancouver: Ronsdale Press, 2005), 99.

(4) Elaine Hedges, “The Needle or the Pen: The Literary Rediscovery of Women’s Textile Work,” Tradition and

the Talents of Women. Ed. Florence Howe, (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1991), 341.

(5) Maureen Daly Goggin, “Introduction,” Women and the Material Culture of Needlework and Textiles. (Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, 2009), 2.

(6) Maureen Daly Goggin, “An Essamplaire Essai on the Rhetoricity of Needlework Sampler-Making: A Contribution to Theorizing and Historicizing Rhetorical Praxis.” Rhetoric Review 21.4 (2002), 312.

(7) Mary Lou Quinlan and Becky Ebenkamp, Brandweek (Adweek Media Group) 44, no. 22 (2003): 20.

(8) Heather Pristash, Inez Schaechterle and Sue Carter Wood, “The Needle as The Pen: Intentionality, Needlework, and the Production of Alternate Discourses of Power,” Women and the Material Culture of Needlework and Textiles, 1750–1950. Ed. Maureen Daly Goggin, (Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, 2009), 16.